In this post, I focus on henna traditions on the Swahili coast of East Africa, especially the archipelagos of Lamu (today part of Kenya) and Zanzibar (today part of Tanzania). I imagine that many henna artists, like me, might associate East Africa simply with 'black henna' and the dangers it poses.

I want to emphasize that while this post will discuss and portray the use of various ‘black henna’ chemical substances, I DO NOT condone the use of ‘black henna’ and urge all my readers to use and support natural henna ONLY.

I want to emphasize that while this post will discuss and portray the use of various ‘black henna’ chemical substances, I DO NOT condone the use of ‘black henna’ and urge all my readers to use and support natural henna ONLY.

So first, a little history (if you want to go straight to the henna pics, I won't be offended — just scroll down a bit!). The Swahili coast has been a centre of trade and culture for over a thousand years. Known as Zanj to medieval Arab traders, East Africa had strong mercantile ties with the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, India, and even China. The Kilwa Sultanate controlled the Swahili coast throughout the Middle Ages, and once it broke up in the 17th century, imperial powers moved in. Zanzibar became part of the Sultanate of Oman in 1698, and a British protectorate in 1890.

The population of the Swahili coast, therefore, is a diverse mix of ethnic and cultural groups, including: Arabs, especially originating in Yemen and Oman; Afro-Arab families, formed as merchants intermarried with local women; African Bantus, including those living in slavery until its abolishment at the end of the 19th century; and Indians, including Hindus, Muslims, and some Parsis.

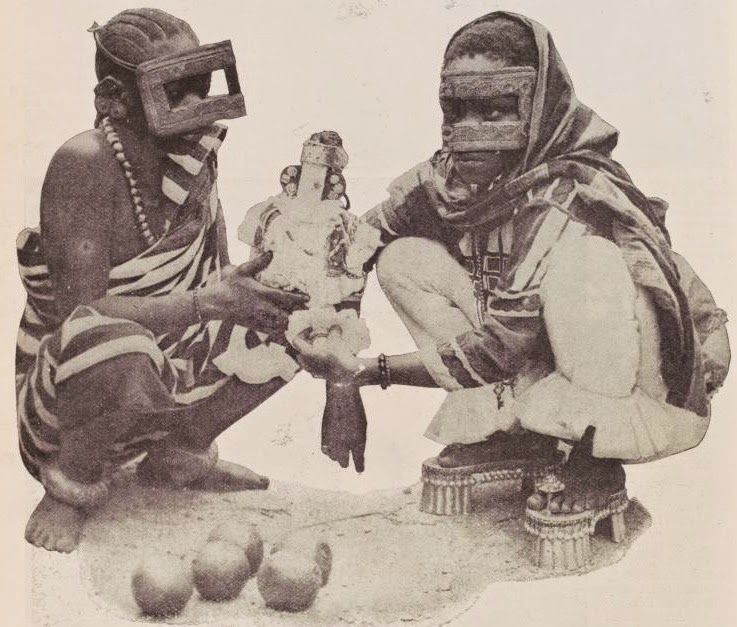

|

| Brahmin Indian woman, Zanzibar, 1900. |

While it is not clear when henna was introduced to East Africa, it was likely that these trading routes brought henna to the Swahili coast quite early on. Patricia Romero Curtin suggests that henna traditions “started among the Hindu women,” 1987, pg. 367, but I suspect that it is far more likely that it was brought by Arab merchants earlier on: probably in the 17th century, or even in the Middle Ages, in the period of the Kilwa Sultanate. Today (as I note in this post) in Swahili henna is known both as mhina / hina, a loanword from the Arabic al-hinna', or mkokowa, referring to the red mangrove (another dye plant that produces a similar colour) — thus supporting the idea that henna was introduced by Arab merchants rather than Indian Hindu migrants (who would have most likely referred to henna as mehndi).

By the 19th century, henna was an essential part of the culture of the Swahili coast, practiced by all the various ethnic groups living there: Arabs, Africans, Indians, Afro-Arabs, etc. For example, Edward Steere, an 19th-century English missionary, records how henna appeared as a part of the wedding festivities for African families in Zanzibar (Steere, 1870, pg. 491):

It is a rule to spend seven days after marriage in the bride's house without going out, during which time the bride's father sends provisions daily, and the bridegroom is scented, and his hands and feet stained with henna, as is usually done by women. This period of seven days is called fungate ['seven'].

|

| Henna-rinsed donkey, Zanzibar, 1952. |

I believe that Steere’s description, of having the wedding henna on display for the seven days after the wedding, is related to a Swahili custom known as ntazanyao which I will discuss below.

Henna was used not only for wedding ceremonies, but as regular cosmetics for men, women, and even for animals. William Ruschenberger, an American navy surgeon, describes a Zanzibari captain originally from Muscat with hennaed nails: “the toenails, as well as those of the fingers, are stained with héna (henna) of a reddish yellow colour” (1838, pg. 29). Hina, "henna" (a loanword from Arabic) is defined in Steere's Swahili dictionary (Steere, 1884, pg. 286, 398):

Henna was used not only for wedding ceremonies, but as regular cosmetics for men, women, and even for animals. William Ruschenberger, an American navy surgeon, describes a Zanzibari captain originally from Muscat with hennaed nails: “the toenails, as well as those of the fingers, are stained with héna (henna) of a reddish yellow colour” (1838, pg. 29). Hina, "henna" (a loanword from Arabic) is defined in Steere's Swahili dictionary (Steere, 1884, pg. 286, 398):

Hina: henna, a very favourite red dye, used by women to dye the palms of their hands and the soles of their feet, often used to dye white donkeys &c. a pale red brown.

Kutona hina: to lay and bind on a plaster of henna until the part is dyed red.

Kutona hina: to lay and bind on a plaster of henna until the part is dyed red.

Zanzibar was apparently known for its hennaed donkeys well into the 20th century. An Anglican nurse/missionary, Ada Sharpe, wrote in the Christian journal African Tidings (1904, pg. 82):

There are countless donkeys in Pemba, many of them very beautiful Muscat donkeys of a light cream colour. If they belong to well-to-do Arabs, they are generally dyed with henna, which makes them a soft terra-cotta colour. This is said to keep off the insects, but I believe it is really done for the sake of appearance more than anything else.

In 1952, Robert Moore reported for National Geographic that “the custom of tinting donkeys with henna had once been fairly popular on Zanzibar — nobody knew just why — but was now dying out” (pg. 278), although I wouldn't be surprised if you could still see it today.

|

| Sayyida Salama, 1907. |

So how was henna done (for people) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries? An excellent description is given in the memoirs of Sayyida Salama bint Said (1844–1924), a daughter of the Sultan of Zanzibar who eloped with her German husband to Europe (and took the name Emily Ruete). She recalls how in her youth the palms and soles were hennaed and wrapped up with leaves (1907, pg. 47):

An important part in the oriental gala toilette is played by henna, derived from the leaves of a shrub… After drying and pulverisation they are mixed with lemon juice and a little water, then kneaded into a dough, which is set out in the sun, and finally treated again with lemon juice to prevent hardening. The recipient lies rigid at full length on her back. First the dough is applied to the feet; their surface remains untouched, but each toe is covered, and the soles and sides. Next a layer of soft leaves is put on, and tightly bandaged down. Then the hands are proceeded with in the same manner exactly. The back of the hand is left free, the edge of the palm and each finger to the first joint being plastered with dough and enswathed.

Motionless does the vain beauty lie on her bed all night, that she be not disfigured through the shifting of the dough. For, mark, only the parts I have specified may be tinted; if henna should appear on the back of the hand, or above the first finger joint, that would be thought hideous... That night the torture begins anew, and the following night once more, since three applications are necessary to produce a rich, dark red, which will keep a month, despite all washing.

I can certainly identify with the desperate attempts to sleep with henna on, without smudging it! Although I'm glad we don't have to pulverize the leaves ourselves anymore.

In the early 20th century, slave women were responsible for preparing and applying the kohl and henna for their masters, for both weddings and regular use, and they were also allowed to use henna themselves (Curtin 1983, pg. 135; Curtin 1984, pg. 879). Sayyida Salama had noted that after the henna was applied, slave women were responsible for taking care of their helpless masters: "No defense is possible against mosquitoes and flies, though the wealthy can have them fanned away by slaves until morning, when the dough is carefully removed" (1907, pg. 47).

In the early 20th century, slave women were responsible for preparing and applying the kohl and henna for their masters, for both weddings and regular use, and they were also allowed to use henna themselves (Curtin 1983, pg. 135; Curtin 1984, pg. 879). Sayyida Salama had noted that after the henna was applied, slave women were responsible for taking care of their helpless masters: "No defense is possible against mosquitoes and flies, though the wealthy can have them fanned away by slaves until morning, when the dough is carefully removed" (1907, pg. 47).

|

| Arab woman, Zanzibar, 1913, with kohl/henna on hands and face. |

We can also see in Sayyida Salama's account that henna was applied multiple times to obtain the deepest possible colour. In later accounts, we see the use of another cosmetic to add a black colour: wanja, or kohl, used on both face and hands. William Harold Ingrams writes (1931, pg. 31):

For marriage, the bride had her hands and feet hennaed — unmarried girls were allowed only to henna their hands, since hennaed feet were seen as provocative and inappropriate for young girls. The henna artist was known as mpambaji [lit. ‘decorator’], an older woman responsible for “the ritual care of the house (which she ‘adorns’) and for ensuring the proper and continued physical and moral purity of its women” — the mpamaji also prepared bodies for funerals (Middleton 1992, 143). Sometimes henna was done by the somo [lit. ‘instructor’] the women who instructs girls in sexual matters and led the initiation rites into womanhood.

The artist used a thin twig to apply the designs, which were for the most part drawn from the local environment (Issa, 2012, pg. 475); designs included:

Françoise Le Guennec-Coppens describes how henna was applied in Lamu in the late 1970s, with the soles being hennaed solidly and designs painted on the palms and fingers (1980, pg. 24):

Their faces are painted with soot in circles and other figures. Generally the outline of the cheek pattern is made by putting wanja (antimony) round the edge of a coffee-cup and pressing it on… Fingers and the nails are dyed with henna, and the palm of the hand is treated like the cheek [i.e. with a pattern in wanja].So historically it appears that palms were adorned with patterns in black and red, with a combination of wanja for the outlines, and the centres filled in with henna. This would seem to be the origin of the aesthetic of black outline / red filling, used in contemporary henna work in East Africa. Today, wanja also refers to the black hair dye used by contemporary artists (which, I repeat, I do not support or condone) in place of the traditional kohl.

For marriage, the bride had her hands and feet hennaed — unmarried girls were allowed only to henna their hands, since hennaed feet were seen as provocative and inappropriate for young girls. The henna artist was known as mpambaji [lit. ‘decorator’], an older woman responsible for “the ritual care of the house (which she ‘adorns’) and for ensuring the proper and continued physical and moral purity of its women” — the mpamaji also prepared bodies for funerals (Middleton 1992, 143). Sometimes henna was done by the somo [lit. ‘instructor’] the women who instructs girls in sexual matters and led the initiation rites into womanhood.

The artist used a thin twig to apply the designs, which were for the most part drawn from the local environment (Issa, 2012, pg. 475); designs included:

- Msumeno = saw (i.e., zigzag)

- Barabara = road

- Majani na Maua = leaves and flowers

- Makorosho = cashew nuts

- Koche = dwarf-palm fruit

- Makuti ya mtende = date leaves

- Yungi-yungi = lotus

- Machenza = mandarin orange

Françoise Le Guennec-Coppens describes how henna was applied in Lamu in the late 1970s, with the soles being hennaed solidly and designs painted on the palms and fingers (1980, pg. 24):

The bottoms of the feet are dyed up to the toe nails. As the edge of the henna comes above the sole, it resembles a brown sole wrapped around the foot. The borders can be decorated with different designs but the soles of the feet are covered completely with the dye. Much more imagination is used to decorate the hands. The designs, different on each hand, can be geometrical or represent flowers and arabesques. They are drawn on the palm and on each finger… Five or six successive layers are applied to ensure that the henna will not fade for at least a month; putting on one layer and letting it dry takes two or three hours, so a minimum of twelve hours is necessary for six layers.

During weddings, while the henna was applied, women sang a type of oral poetry called vugo [‘buffalo horns,’ from the instruments used], spontaneous rhymed songs that could reinforce traditional values or serve as pointed jabs at various members of the bridal party (Eastman, 1984, pp. 326-328). Other songs prepared the bride for her new social role and offered advice from older family members.

|

| Bi Kidude, the barefoot diva of Zanzibar. |

Born to a coconut seller sometime in the early 20th century, Bi Kidude was a pioneering Zanzibari singer of taarab [a genre of Arabic music inspiring emotional responses from the audience, famously associated with Umm Kulthum] who performed around the world for decades and passed away in 2013 at an unknown age, likely well over 100.

Bi Kidude was an icon of Zanzibari style and culture, and an activist for women's rights. She was also famous for having never worn shoes, saying that "as soon as you start to wear shoes you become weak." Check out her music and interviews!

|

| Bi Kidude's feet, adorned with henna and wanja, Luc Vekemans, 2006. |

In the early 20th century, the bride's henna was traditionally shown off after the wedding in a ritual known as ntazanyao [“tips of her toes”], which began the fungate [seven-day honeymoon]. Traditionally, at the ntazanyao the bride’s beauty was ‘displayed’ with all her henna, including the soles of her feet; she had to sit motionless, with her eyes closed, to her guests' admiration (Middleton 1992, pg. 149; this is an interesting parallel to a Libyan Jewish henna ritual). Today the ntazanyao, if celebrated at all, has become a big party.

|

| Swahili women with hennaed fingers, Zanzibar, 1914. |

Henna was also used in East Africa for circumcisions, which usually took place between 18 months to five years, but sometimes past six and even into a child’s teens. The child was given their new cicumcision name [jina la kutahirawa], and was dressed in new clothes, painted with wanja, and had their hands and feet hennaed; they were then seated on the veranda to greet relatives and friends and receive gifts (Trimingham, 1964, pg. 130).

Henna is also used by wahanithi, gender-non-conforming individuals who might identify as homosexual men, others as trans women, and others as simply hanithi (the word comes from the Arabic mukhannath, about whom I have written before). Many wear male clothes, restricting their feminine ornamentation to kohled eyes and hennaed nails, but others live almost fully as women: Larsen describes one hanithi named Sabri who “partly dresses in women’s clothes, puts on make-up, colours his nails with henna and decorates his hands with both henna and wanja” (Larsen, 2008, pg. 118). Most men on the Swahili Coast today, even grooms, avoid henna for fear of appearing to be hanithi.

|

| Henna competition in Lamu, 2011. Photo by Eric Lafforgue. |

So let's talk a little about the style of henna designs in East Africa today. In the historical sources, we saw the repeated layering of henna to achieve a dark stain, and the use of natural henna decorated with outlines in black kohl, known as wanja. In the late 80s this began to be replaced with black hair dye, known colloquially as nyeusi [Swahili for 'peacock'] or pico [from the English 'peacock'] after the most common brand, Peacock (Young 1992, pg. 17). Of course, the black PPD in those hair dyes is a dangerous toxin, and its use causes many injuries and health problems for both locals and tourists (Cartwright-Jones, 2014, ch. 1).

|

| Adding the two-tone with natural henna. Photo by David Coulson. |

When looking at the henna that’s done today on the Swahili coast, the vast majority of it is ‘two-tone’ black and red. Natural henna is still used, of course, but it seems like most often it is paired with black chemical dye, although occasionally all-natural henna is seen.

The most popular designs seem to be strips of stylized flowers with big open petals and leaves, outlined in black and filled in red, arranged in a flowing layout reminiscent of some Gulf-style work... Of course, this is no surprise given the continued cultural and commercial ties between the Swahili coast and the Arabian peninsula. For brides it usually extends past the elbow and sometimes even up to the shoulder and across the chest as well — this style is known as bibi harusi henna.

|

| Henna in Msambweni, Kenya, 2012. Photo by Molly Layde. |

|

| Patience Ray, an American exchange student in Kenya, with natural henna in bibi harusi style, 2010. |

|

| A Tanzanian bride, Pangani. Photo by Klaus Hartung, 2012. |

Some of the contemporary work is artistically quite fine, although I must say that a lot of the pictures I see online, especially of henna done for tourists, looks fairly sloppy to me. There is certainly potential for amazing work, but unfortunately the use of dangerous ‘black henna,’ combined with high numbers of (generally ignorant) tourists demanding ‘quick and dirty’ designs is hurting the future of these beautiful traditions (a theme explored more fully in Cartwright-Jones 2014).

|

| Fine work, unfortunately with 'black henna,' Lamu, 2011. Photo by Eric Lafforgue. |

It's true that you may not be able to get as striking a contrast between the 'black' and the 'red', especially on the upper arm; but I think the benefits of using traditional natural henna — such as avoiding the scars, burns, and lifelong PPD sensitivity acquired by using black henna — are more than worth it.

Here's an example I did, inspired by a photo of 'black-and-red' henna from Lamu:

So mix up your "very favourite red dye," as Steere writes, and get hennaing!

Bibliography

Note: In addition to these published sources, I also read a lot of articles and blogposts online. Here are some of the most helpful:

Mambo Magazine

ZanziNews

Voices of Africa

Kenya Standard

Arkansas State University

Cartwright-Jones, Catherine. The Geographies of the Black Henna Meme and the Epidemic of Para-phenylenediamine Sensitization. PhD dissertation (unpublished), Kent State University, 2014.

Curtin, Patricia Romero. Laboratory for the Oral History of Slavery: The Island of Lamu on the Kenya Coast. The American Historical Review, Vol. 88, No. 4, 1983, pp. 858-882.

Curtin, Patricia Romero. Weddings in Lamu, Kenya: An Example of Social and Economic Change. Cahiers d'Études Africaines, Vol. 24, Cahier 94, 1984, pp. 131-155.

Curtin, Patricia Romero. Possible Sources for the Origin of Gold as an Economic and Social Vehicle for Women in Lamu (Kenya). Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 57, No. 3, 1987, pp. 364- 376.

Eastman, Carol. An Ethnography of Swahili Expressive Culture. Research in African Literatures, Vol. 15, No. 3, 1984, pp. 313-340.

Fair, Laura. Dressing Up: Clothing, Class, and Gender in Post-Abolition Zanzibar. Journal of African History, Vol. 39, 1998, pp. 63-94.

Ingrams, William Harold. Zanzibar: Its History and Its People. Oxford: Frank Cass, 1931.

Issa, Amina. Wedding Ceremonies and Cultural Exchange in an Indian Ocean Port City: the case of Zanzibar Town. Social Dynamics: a Journal of African Studies, Vol. 38, no. 3, 2012, pp. 467-478.

Larsen, Kjersti. Where Humans And Spirits Meet: The Politics of Rituals and Identified Spirits in Zanzibar. Berghahn Books, 2008.

Le Guennec-Coppens, Françoise. Wedding Customs in Lamu. Lamu Society, 1980

Middleton, John. The World of the Swahili: An African Mercantile Civilization. Yale University, 1992.

Moore, William Robert. Clove-Scented Zanzibar. National Geographic Magazine, Vol. 101, no. 2, February 1952, pp. 261-278.

Ruete, Emily. Memoirs of an Arabian Princess. New York: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1907.

Ruschenberger, William. Narrative of a Voyage Round the World, During the Years 1835, 36, and 37. London: Richard Bentley, 1838.

Sharpe, Ada. Medical News. African Tidings, Vol. 13, 1904.

Steere, Edward. Swahili Tales As Told by Natives of Zanzibar. London: Bell and Daldy, 1870.

Steere, Edward. A Handbook of the Swahili Language As Spoken at Zanzibar (ed. A. C. Madan). 3rd ed. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1884.

Thompson, Katrina Daly. How to Be a Good Muslim Wife: Women’s Performance of Islamic Authority during Swahili Weddings. Journal of Religion in Africa, Vol. 41, 2011, pp. 427-448.

Trimingham, John Spencer. Islam in East Africa. Clarendon Press, 1964.

Young, Kelly. Henna in Islamic Society: A Study in Lamu. Kenya Past and Present, Vol. 24, 1992, pp. 17-18.

No comments:

Post a Comment